Street overlooking one of the entrances to Kampung Plampitan.

Photo Credit: Aarti Kawlra, Surabaya, Indonesia (2024)

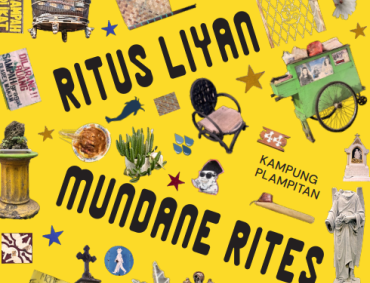

Ritus Liyan (Mundane Rites): Some Intimations on Process

Ritus Liyan, a dialogic, multi-sited exhibition within Kampung Plampitan initiated by the Airlangga Institute for Indian Ocean Crossroads (AIIOC) and HAB, was the outcome of long-term and focused interactions between urban researchers, activists, artists, curators, and residents of Plampitan, Surabaya.

In this excerpt from the exhibition catalogue, Academic Director Aarti Kawlra reflects on the process behind the exhibition, its aim to place the kampung and its residents at the centre, and the conversations that naturally came about in creating artistic expressions of their daily rituals or as it came to be known, their mundane rites.

Kampungs or urban neighbourhoods in Surabaya in East Java have been entry points of research on Asian cities, anchoring the collaboration between IIAS and UNAIR. Dating back to the inaugural meeting of the South-East Asia Neighbourhoods Network (SEANNET) in 2017 at Kampung Peneleh, [1] the local and regional level inquiries led to a number of joint publications on the city of Surabaya. These include examining the historical role of Surabaya’s kampungs in nation building, or in the making of Surabaya as a river/port city at the crossroads of international trade. [2] Later, following the COVID crisis, the collaboration between UNAIR and IIAS took a new, institutional building dimension with the inception of the Airlangga Institute for Indian Ocean Crossroads or AIIOC.

From its inception, AIIOC was envisioned as a new space of mediation between disciplines and between academia and society. The idea of conducting an art-in-society workshop came from the University of Airlangga’s professor Lina Puryanti, as she set about applying for a grant from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology for a global-local art exhibition as an inaugural activity of the newly constituted AIIOC. It was Lina’s energetic vision, not only to build capacities within the AIIOC team, in preparation for its first international conference and public outreach festival ICAS 13 but also, to test the trans-disciplinary, community-based, collaborative approaches developed over the years at IIAS, especially in the realm of situated-learning pedagogies as developed by its Humanities Across Borders (HAB) program. It was against the backdrop of the institutional support of an IIAS-like facilitation platform, i.e. AIIOC, and research focus of perceiving the kampung as a counter-discourse and space of resistance to the dominant urban development paradigm, that we sought to locate our joint interest, once again, within Surabaya’s kampungs.

The open call that went out in early February was to anyone interested in situation their artistic practice in the vibrant context of a kampung with the active participation of its residents. The workshop eventually took place in the Balai RW O2 or meeting hall of the administrative divisional office of Kampung Plampitan, whose leadership is occupied by a woman, Ibu Suminah. It was conceived as both an art residency as well as a community enmeshed, creative collaboration conducted in and around courtyards, homes, verandahs, vacant plots, hero-graves, and by-lanes of Kampung Plampitan. [3]

Residents of Plampitan watching a football game with Ritus Lyan artists after the workshop.

Aarti Kawlra, Surabaya, Indonesia (2024)

Plampitan’s active citizens

It was more than chance that led the residents of Plampitan to welcome the workshop and exhibition. They were eager to build the collaborative platform and participate in all discussions and activities that ensued. Ritus Liyan was the outcome of reciprocal interactions and gradual strengthening of existing ties with the residents of Plampitan. As a student at UNAIR, Anitha Silva, urban researcher-activist and program manager of Ritus Liyan, first time visited her cousin’s house at Plampitan VII. “I always used the pedestrian Bungkuk bridge to cross over the Kali Mas to enter Plampitan. It is very conveniently located in the city centre of Surabaya. During my university days, it was a safe haven to escape from the heat and to visit my family house for free food.” In 2011, Surabaya-based urban designer and curator of Ritus Liyan, Bintang Putra of the Operations for Habitat Studies (OHS), with Japanese urban planner and researcher Kenta Kishi, worked with Plampitan residents to create an exhibition-platform “to raise questions and bring people together to identify creative solutions that will lead toward a more sustainable future for local communities.” [4]

In 2019, as part of her project of producing counter maps of old neighborhoods in Surabaya through public walkabouts,[5] Anitha’s regular visits to Plampitan made her conscious of its everyday life, and especially the role of women in the kampung’s economy, “I became more aware of where women go to buy fresh vegetables, which kiosk has the finest robusta coffee brew, which warung serves the most delicious (and cheapest) lunch, and in which entrance alleyway the sign “Turn off your motorbike and walk” is located.”

AIIOC’s vision of embedding the ICAS 13 festival in the local realities of Surabaya was therefore uppermost for Ayos Purwoaji, the festival director of ICAS 13. Ayos’s plan was not only to design Ritus Liyan as a pre-ICAS event but also to fulfil community entry protocols that are necessary before any international conference that aims to integrate a festival within it. It was through official channels of the local municipal government that Ayos, Anitha and Bintang were led to the active citizens of Plampitan, the women of RW II. It was the niece of Roeslan Abdulgani, a prominent minister in the Indonesian government (retired in 1971) and resident of Plampitan, Ibu Rahma, who led the team to Plampitan RW II. According to Anitha, “One of the women, Ibu Ida, told me many times, that our program will be successful, because we are here…. As program manager, I knew I would need all the support I could get in Plampitan. The workshop has been successful because of the continuous support of Ibu Rahma & Ibu Erwin (RT 4), Ibu Suminah, Ibu Ida, Ibu Ita, Ibu Nana (RT 7), Ibu Titis & Ibu Leni (RT 1), and Ibu Darmi (RT 3).”

In his memoir, Masa Kecilku di Surabaya, translated by William H Frederick as “My Childhood World”, Abdulgani writes, “Plampitan was not the only kampung in this part of Surabaya. There were Peneleh, Ngemplak, Jagalan, Kalianyar, Pandean, and many others, covering about fourteen square kilometres in all.” It was this photocopy of the original book borrowed from Abdulgani’s personal library and family archive, bound in yellow and fondly referred to as the buku kuning or ‘yellow book’, that exchanged multiple hands and was poured over continuously during the workshop. Many of Abdulgani’s stories take place amidst narrow gang or dirt alleyways, beneath the shade of ancient trees, and beside the graves of ancestors. The autobiography serves as an account of the quotidian history and life struggles of families living in the kampung and makes a significant contribution to the history of Plampitan from the vantage of its residents:

“On the east side of Plampitan grew an enormous banyan, and under it was the sacred grave of Kiyai Pasopati. Still further to the east were the graves of the ordinary folk, a reminder of the days when people were buried in their own yards instead of in regular cemeteries like Botoputih, Tembok, and Kapaskrampung. Mother, who had a good sense of humour, used to explain that once, in the days of the Buddha, each house in Surabaya had had its own plot and a person could therefore be buried in his own ground. But one day, the Jogodolok appeared out of the blue. Crash! The whole city was shaken as if by an earthquake. And that was how all the houses came to be pushed up so close against one another..” [6]

The themes from the yellow book were inspirational for workshop participants and gently guided the research and expression of Ritus Liyan.

Residents of Plampitan and the Ritus Lyan artists in conversation about their collaborative artistic projects.

Aarti Kawlra, Surabaya, Indonesia (2024)

Building a space for dialogue

The question of commencing the workshop during Ramadhan was among our first concerns, especially given the tight exhibition schedule leading up to the final opening date of May 24, 2024. It was decided to use the morning sessions for discussions and research and to schedule all meetings and walkabouts in the kampung for the afternoon, when the heat is less intense and when the residents are also outdoors preparing the Iftar, or evening meal, that marks the end of the collective daily fasting period. The evening “breaking the fast” snacks, drinks, and meals, were especially prepared for the workshop by women entrepreneurs from the kampung who happily took into account special requests. Slowly the gazebo adjacent to the games field became the spot where the daily closing ritual of the workshop was performed - sharing food, joking, stretching, smoking whilst young children from homes nearby ventured out to play, or watch us with curiosity. It was in this open space, as well as on the tiled floor of the verandah of the balai overlooking the arched bridge over the Kali Mas, where workshop participants mingled, with one another and with the kampung residents, amidst endless puffs of smoke and coffee. It was here that the seemingly random sights, sounds tastes, photographs, sketches, mind maps, experiences, conversations, and reflections, coalesced into the insights that eventually came to underpin the collective expression, Ritus Liyan.

The walkabouts in the alleyways of the kampung were strolls in the company of other participants, many of whom are local artists and researchers, and others who traveled from outside Surabaya. They were moments and images of both surprise and recognition, reflection and respite, tidy and busy, abandoned and tended to, but always mellow, orderly and inviting. Our first impressions, from the photographs many of us took, were of the pigeon trainers on the pedestrian bridge over Kali Mas, the busy street with lorries loading cargo to be taken to the harbor, the verandah of the balai crowded with footwear and men playing chess or watching football on the communal TV, and inside, as you move further into the alleys, the symmetrical row of hanging plants growing out of inverted recycled plastic water containers, rubbish bins made from re-purposed rubber tires, painted terracotta, washed laundry flapping in single-file along narrow semi-covered passages on the street, a once parked brightly painted becak or cycle rickshaw now being driven and followed by a group of children, empty Chinese-style bird cages hanging in most home entrances, the old mosque building, the tiled roofs of homes, the colonial style homes with entrance pillars and facades, different types of fences, the well-maintained hero-graves, signboards of different kinds like the Pesantren or youth hostel and school, the red door with the sign saying Ketok Pelan or “knock softly”, Ada bayi tidur, “there is a baby sleeping”, passerby women residents delivering homemade and packaged fish cakes (kerupuk ikan payus), windows that open up as food stalls or warungs with make shift benches for customers, the shade islands especially made for resting outdoors, the wall nursery, the old trees and sapling groves, political graffiti and posters ….

The time we spent sharing stories, listening, reading, and discussing inside the balai was also very important. For a start, we had a very conducive workspace within the kampung, equipped with water, coffee, an overhead projector, a pedestal fan, and walls lined with framed portraits of community elders and leaders. We met with Ibu Suminah, who shared with us her story of making batik cloths with her team of other women batik makers in the kampung. Her son, Danar Dwiputra, is an adept animation artist-storywriter, maker, and collector of wayang shadow or leather puppets, in addition to being a batik artist. Through their presentations and stories, we learnt about the injunction against wayang performances in the kampung (It is uncertain when it occurred) and how the wayang jek dong is the voice and language (Bahasa) of the people of the kampung. We soon realised that aspects from a deep past like mythic symbols, creatures, morals and tales, everyday social norms, and administrative rules, commingle in the kampung, are continually put under the spotlight to be re-interpreted in the light of its present, and or future. There were other residents of the kampung who joined us in the balai, sometimes casually to walk in and listen, and other times to themselves talk and share their stories.

Most of the exercises facilitated by us, i.e. Bintang, Ayos, Anitha, and myself, involved place-based, in situ thinking and doing. This meant that the participants were willing to enter the everyday lives of the people of Plampitan by being present in the human-geographical context of the kampung. The idea was to learn about Plampitan by walking in it, spending time there, asking open-ended questions that would give space for residents to share freely, making friends, and eventually becoming comfortable there. We wanted them to observe the different (familial, work, collective, individual) routines, activities, and daily itineraries of the residents that interested them, and to map these with the time of day and the spaces and places in which they occurred. Most of the projects showcased at different sites located in Plampitan emerged through this gradual process of immersion. This involved the sharing of food, exchanging stories, playing, and thinking together with the residents toward mutually motivating yet self-actualising goals. Each of the artists who eventually presented their work at Ritus Liyan did so in their unique way, and there was no single approach to how they could have arrived at their articulation of mundane rites. Yet, each has been through a journey of inquiry, an interruption of their own beliefs and knowledge, and arrived at a deeper understanding and appreciation of their work practice in the process of this brief encounter with the warga (residents) of Plampitan.

A few of the Ritus Lyan collaborative artistic projects on display in Plampitan, showcasing their stories and interpretation of the mundane rites that make up life in the kampung.

AIIOC, Surabaya, Indonesia (2024)

Going past the methods conundrum

The original title of the workshop was “Relative Intersection”, gesturing towards a multi-dimensional intersection between artistic practices, local knowledge, and citizens’ expressions of civic responsibility and change. Speaking from an academic point of view, this workshop leading up to the exhibition and the catalogue, is an example of a multidisciplinary, even trans-disciplinary, approach to everyday knowledge of a kampung and its environs in Surabaya. As an exercise in situated learning beyond the classroom, it is an attempt to blur the binary of the student and the teacher, author and audience, expertise, and communal knowing.

The exhibition and multi-sited canvas that emerged with the coming together of each of the art-in-society projects in Ritus Liyan can only be viewed as a palimpsest, a momentary inscription upon layers of previous writings. Perhaps what we are celebrating here is the moment when the artist-interlocutors became warga and the warga became artist-interlocutors. Our aim was a kind of re-scripting of the kampung in dialogue with its people, places, objects, and activities; not necessarily to make it something exotic or exceptional, but to draw attention to the daily life and dignity of the people who live there, as they interacted with the workshop participants, to reciprocally influence each other’s capacity for self-revision.

Beyond disciplinary knowledge, Ritus Liyan articulates a self that is continually changing and hence always living, in the words of Virginia Woolf. The collaborative process, in many ways, celebrates the refusal to remain fixated on a place, an outcome, a belief, or a value. Together, it is an honouring of its opposite, the courage and openness to forget the past, to rethink our cultural and familial conditioning, repurpose our losses, and share our gains, even as one continues to enunciate individual and collective priorities, in the here and now. On the question of aesthetics, Ritus Liyan points to values countering those of productive efficiency, or those of orderly-disorderly proportions. The everyday micro-acts of living and relating offer serendipity, ambiguity, and unfinished modalities of being-in-the-world. A “liquid modernity”, as Zymunt Bauman observed of the current state of our globalised world.

Endnotes

[1] Adrian Perkasa traces the pre-history of IIAS’s engagement with UNAIR in Surabaya, especially beginning with this event in Kampung Peneleh in IIAS Newsletter #98

[2] Some recent publications include Perkasa, Adrian, Rita Padawangi, and Eka Nurul Farida. “The kampung, the city and the nation: Bhinneka Tunggal Ika in the everyday urban life of Kampung Peneleh, Surabaya, Indonesia.” Asia Pacific Viewpoint 63.3 (2022): 364-378; Padawangi, Rita, Paul Rabé, and Adrian Perkasa. River Cities in Asia: Waterways in Urban Development and History. Amsterdam University Press, 2022.

[3] Kampung Plampitan is wrapped on its southern edge by the river Kali Mas. On the north, Plampitan spreads around a cemetery dating back to the Dutch colonial period, which in turn shares a boundary wall with Kampung Peneleh. Further north of Kampung Peneleh, and separated by Jalan Makam Peneleh, is Kampung Pandean. All three settlements are situated along the river Kali Mas, reminding us of their historical participation in the wider economic activities of the port of Surabaya.

[5] Counter-mapping Surabaya: Designing ‘cities within the city’ (2023)

[6] Ruslan Abdulgani, My Childhood World, edited and translated by W.H. Frederick, nd: 114